Creative Fitness: A Framework for the Explicit Teaching of Creative Skills

AITSL Focus Areas: Understand how students learn (1.2); Differentiate teaching to meet the specific learning needs of students (1.5); Develop teaching activities that incorporate differentiated strategies to engage all learners (2.1); ; Include a range of teaching strategies (3.3); Use effective classroom communication to support student participation and agency (3.5); Assess student learning and provide timely, constructive feedback (5.1); Engage in professional learning and improve practice in collaboration with colleagues (6.2)

SITUATION

In academically selective secondary contexts, critical thinking is explicitly scaffolded across subjects—yet creativity often remains under-taught, under-valued, or misperceived as either a “soft skill” or an innate trait. Many of my students, while highly capable, lacked the confidence or process awareness to take creative risks. I observed a tendency to conflate creativity with perfection, rather than exploration, iteration, and play.

Motivated by this gap, I set out to build a framework for explicitly teaching creativity as a multidimensional skillset—one that could be practised and strengthened over time, much like physical fitness.

ACTION

Drawing on Greg Glassman’s Ten General Physical Skills (CrossFit, 2002) and aligning with research by Amabile (1996), Kaufman & Beghetto (2009), and Ritchhart (2015), I developed a model of Eleven Creative Modal Domains. Each domain isolates a specific facet of creative behaviour, such as fluency, originality, or empathy. Together, they form a comprehensive and trainable structure for creative growth.

I introduced weekly micro-tasks in every class—short, structured creative prompts that isolate one domain and invite students into fast, low-stakes creative play. Each task follows a gradual release model:

I do: I model or narrate a version of the task.

We do: We experiment, share provocations, or remix together.

You do: Students respond, reflect, and upload their work into a “Creative Fitness” portfolio folder.

These tasks built a metacognitive vocabulary around creativity, providing students with a clearer understanding of how creative thinking works and how they could improve it.

THE ELEVEN MODAL DOMAINS OF CREATIVITY

1. Fluency – Generating Many Ideas

The ability to produce multiple ideas quickly without self-censorship.

Task: Idea Sprint – 3 minutes to generate 20 ideas for redesigning a lunchbox.

Focus: Divergent thinking, quantity over quality.

2. Originality – Producing the Unexpected

Creating surprising or novel ideas that deviate from convention.

Task: Invert It – Reverse the function of a common object (e.g., a lamp that absorbs light).

Focus: Pattern disruption, novelty generation.

3. Flexibility – Switching Perspectives or Categories

Thinking across different disciplines, metaphors, or user perspectives.

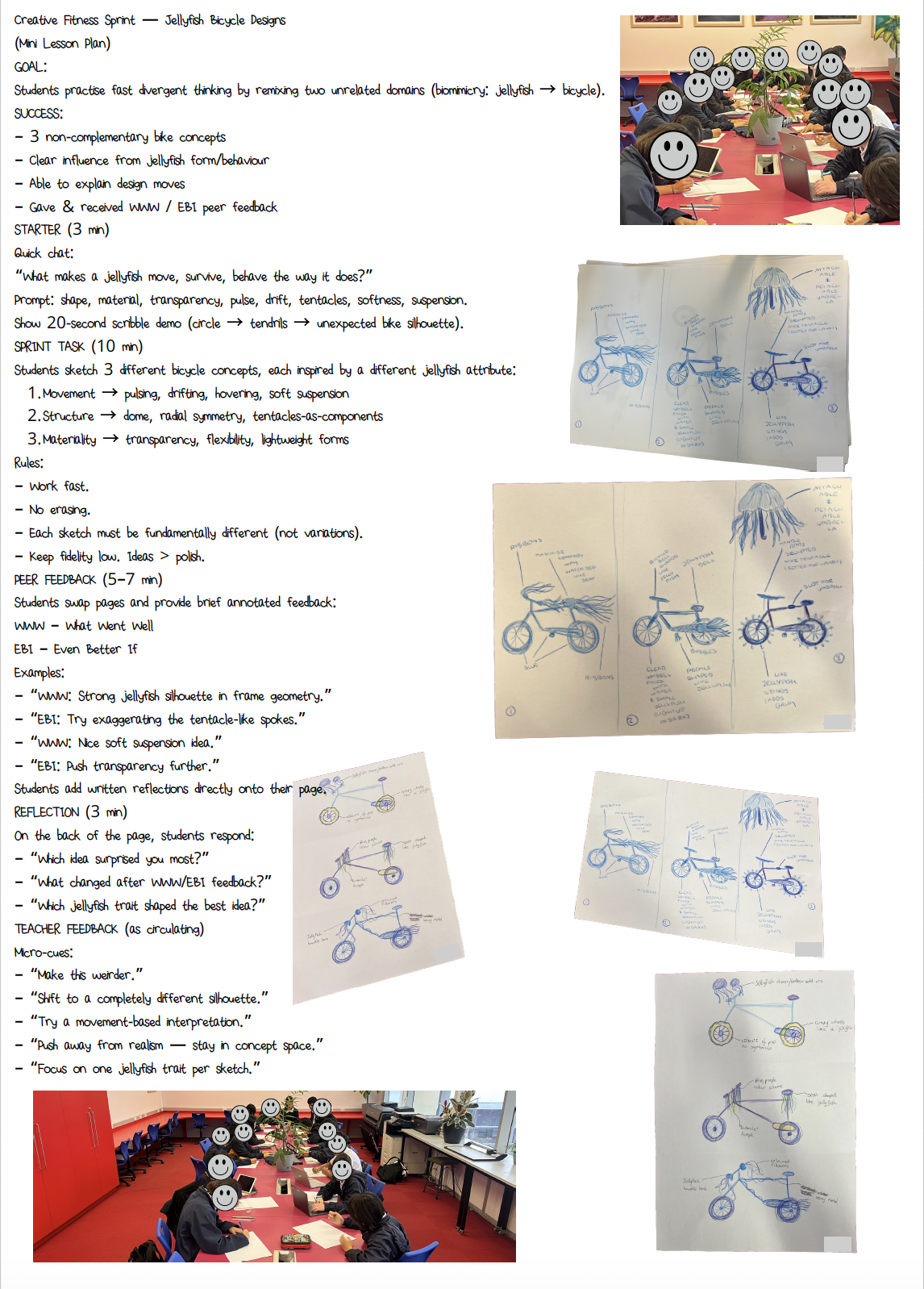

Task: Design by Analogy – Redesign a bicycle inspired by a bird, a jellyfish, and a city.

Focus: Cognitive agility, lateral transfer.

4. Elaboration – Developing Ideas in Detail

Adding richness, depth, and layered meaning to ideas.

Task: Tiny to Tower – Start with a sketch, develop five additional layers (texture, emotion, symbolism, function, context).

Focus: Iteration, refinement.

5. Resilience – Bouncing Back from Creative Setbacks

Persisting through uncertainty, ambiguity, or perceived failure.

Task: Creative Bounce – Revisit a “failed” design and remix it into something new.

Focus: Growth mindset, process over outcome.

6. Risk-Taking – Embracing Uncertainty and Vulnerability

Making bold or unconventional creative decisions.

Task: Ugly Design Challenge – Make the worst ad you can, then justify it.

Focus: Vulnerability, critique of norms.

7. Collaboration – Building Ideas Together

Creating with and through others, embracing collective authorship.

Task: Silent Pass-Along – Collaborative drawing, passed and evolved every two minutes.

Focus: Co-creation, group flow.

8. Reflection – Metacognitive Creative Thinking

Stepping back to understand and improve the creative process.

Task: Voice-over Review – Narrate your design choices in a one-minute voice memo.

Focus: Self-awareness, decision-making.

9. Discipline – Sustained Creative Practice

Commitment to process, structure, and iteration over time.

Task: 1% Challenge – Improve the same design by 1% over five lessons.

Focus: Long-term focus, creative endurance.

10. Empathy – Designing With Others in Mind

Understanding and imagining the needs of real or fictional users.

Task: Design for a Stranger – Create a product for a random persona (e.g., “a visually impaired teenager in a loud city”).

Focus: User-centred design, compassion.

11. Creative Speed – Fast Ideation Under Pressure

Quick generation and execution of ideas under tight constraints.

Task: 30-Second Creative Blitz – Redesign a backpack for a time traveller in under 30 seconds. Upload immediately.

Focus: Flow, fast decision-making, intuitive response.

OUTCOME

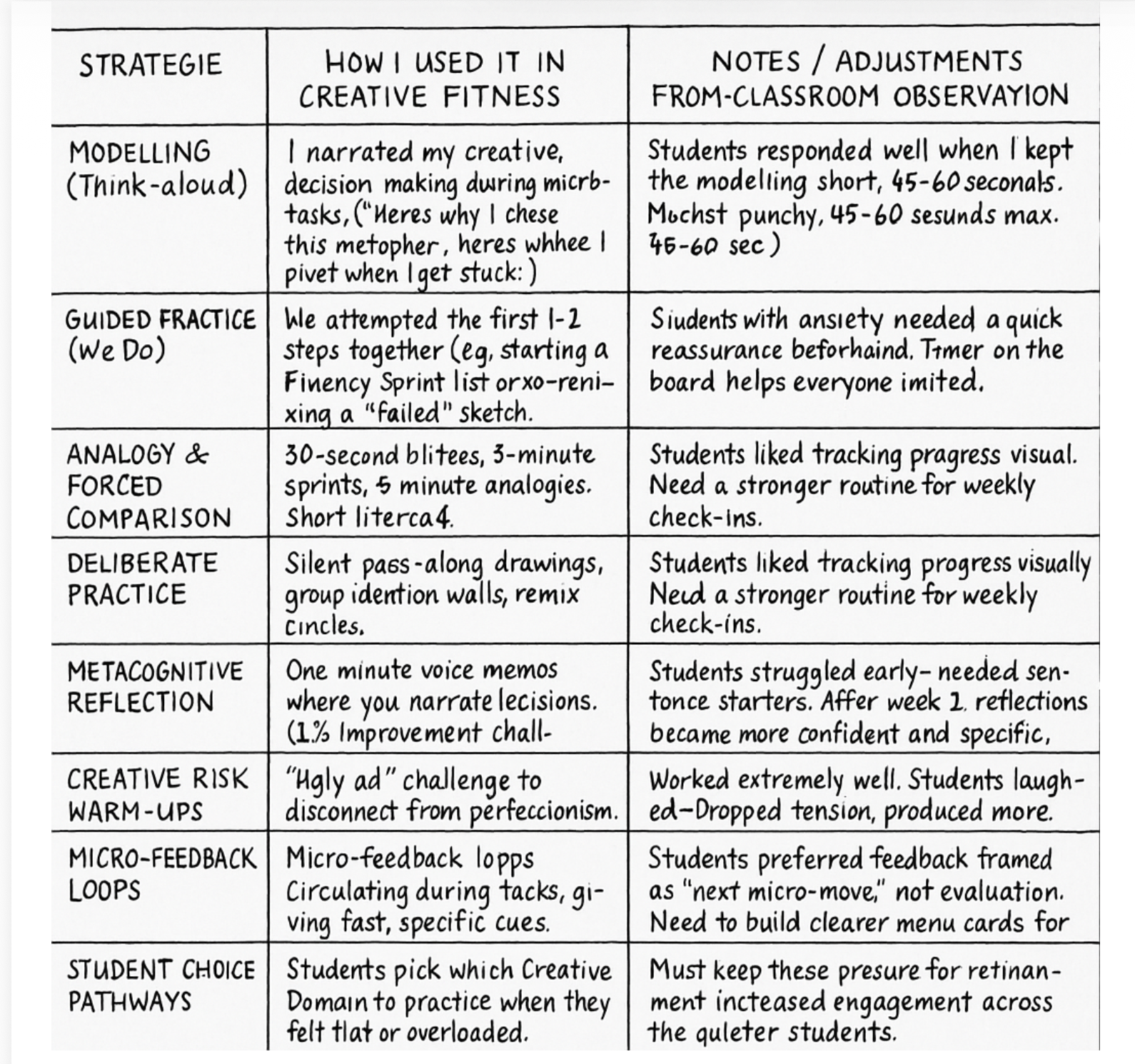

The implementation of this creativity framework is in its early stages and represents a work in progress rather than a finished product. I am currently piloting the Eleven Modal Domains of Creativity across all my classes, using weekly micro-tasks to introduce and reinforce each domain in short, focused bursts. While initial student engagement has been positive—particularly with tasks that prioritise speed, humour, or metaphor—I am still actively testing the model’s structure and language.

Student reflections are helping me assess which domains resonate most clearly and how creative behaviours develop when they are named, isolated, and practiced. I am also gathering informal feedback from my Year 10 and Year 11 classes to gauge how these tasks influence their confidence and risk tolerance in longer design projects.

In parallel, I’ve begun discussing this framework with my line manager and design teaching colleagues. We’re exploring whether this could evolve into a more formalised tool for building creativity across the curriculum, including the possibility of a shared Creative Fitness Task Bank, teacher training modules, or even contribution to wider professional learning for Design educators in Western Australia.

This evidence set reflects an early-stage initiative guided by a clear belief: that creativity, like any essential skill, can be taught, practiced, and refined when approached with care, intention, and shared language. My next steps involve deeper documentation of student growth, refinement of domain definitions, and continued dialogue with peers to understand the broader applicability of this work.

Annotated evidence

1.2 – Understand how students learn

In 2023, I noticed a student who consistently produced highly polished, technically refined work. Their outcomes were always impressive, but what stood out to me was that their creative choices seemed shaped by a strong awareness of what teachers expected, rather than by a drive to explore personal ideas. This observation helped me recognise a wider pattern in academically selective contexts: many students learn to equate creativity with producing the “right” kind of excellence. Even when invited to explore personal narratives, they often preferred the security of familiar success. That insight became the starting point for my Creative Fitness framework. By scaffolding creativity into explicit, low-stakes domains—like fluency, originality, or resilience—I aimed to create space where students could practise creative risk-taking without fear of losing achievement. The goal was to help capable learners see creativity not just as compliance with high standards, but as a skill they could strengthen through experimentation and play.

1.5 – Differentiate teaching to meet the specific learning needs of students.

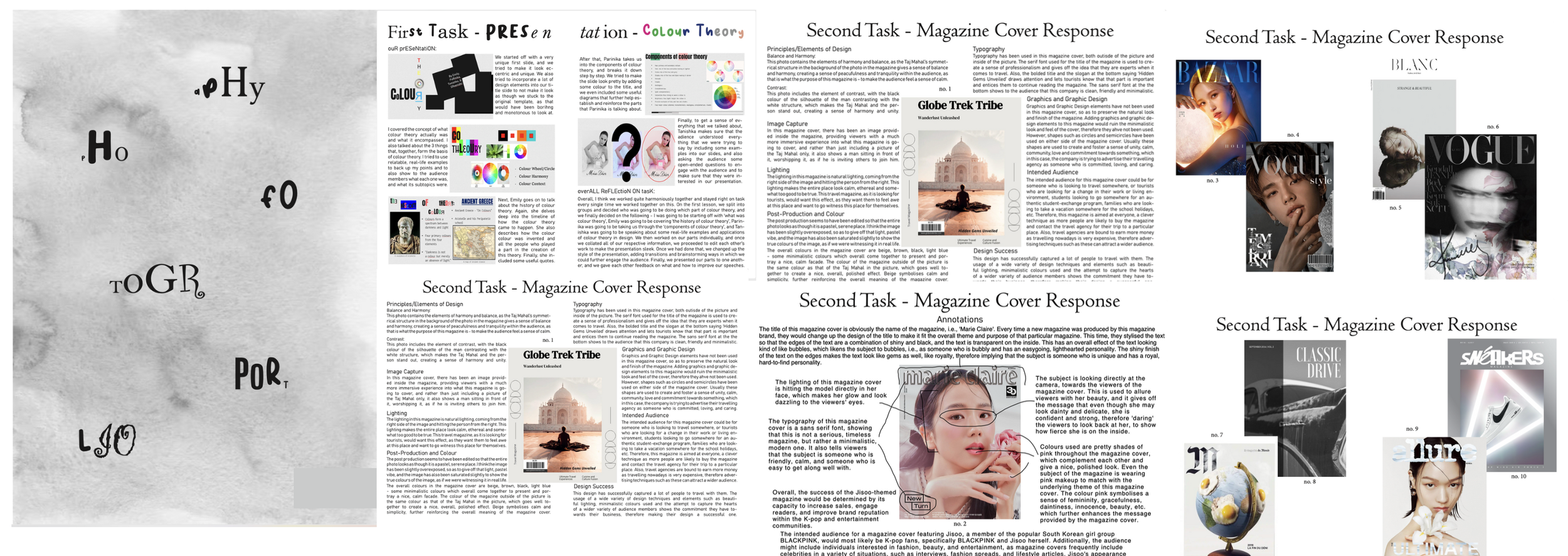

The wide contrast between Student 1 and Student 2 in this same task highlights the need for differentiation. Student 1 approached the project with confidence, producing a detailed and polished portfolio that demonstrated strong organisation and refinement. Student 2, meanwhile, required more guidance to generate, develop, and extend ideas. The Creative Fitness framework provided a way to meet both sets of needs. For students like Student 1, domains such as originality and risk-taking pushed them beyond polish toward experimentation. For students like Student 2, domains such as fluency and resilience gave structured entry points that supported idea generation and persistence without fear of failure. By rotating through the Eleven Modal Domains, I ensured each learner had opportunities to grow in ways that matched their current strengths and needs, while also being stretched into less familiar creative behaviours. This meant students working at very different levels could both experience progress and agency within the same task.

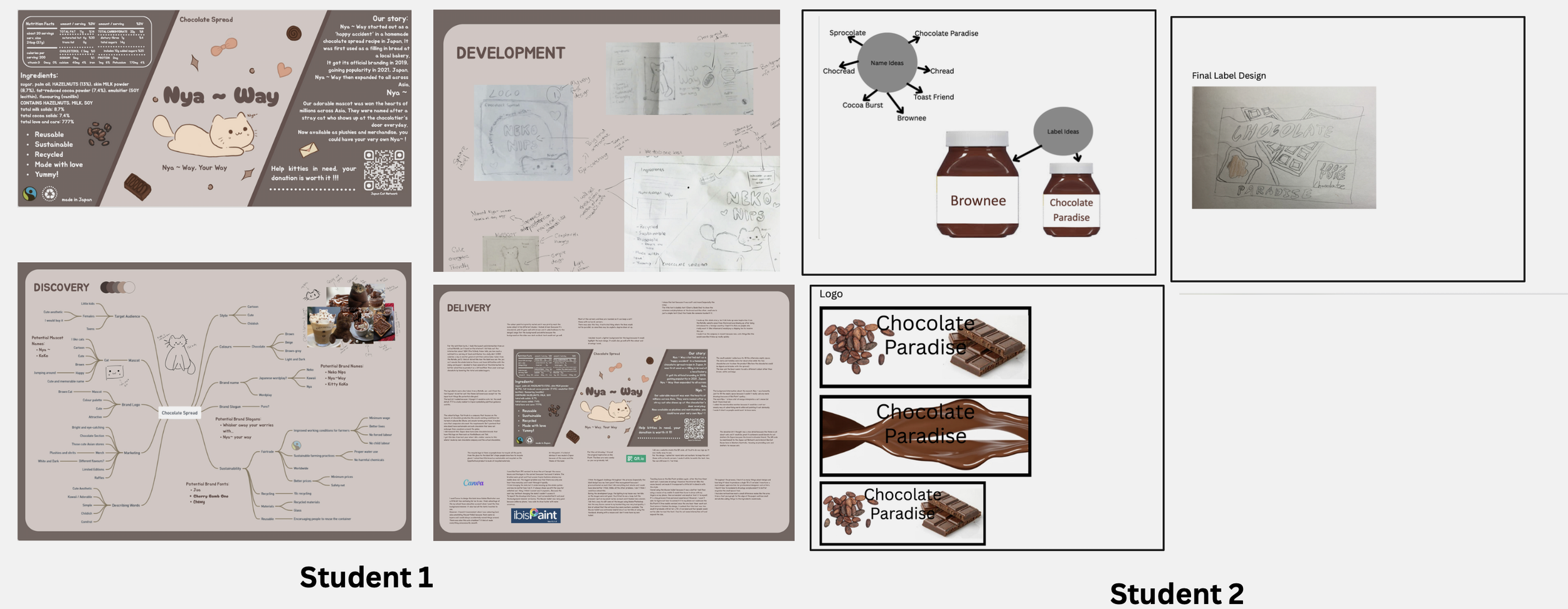

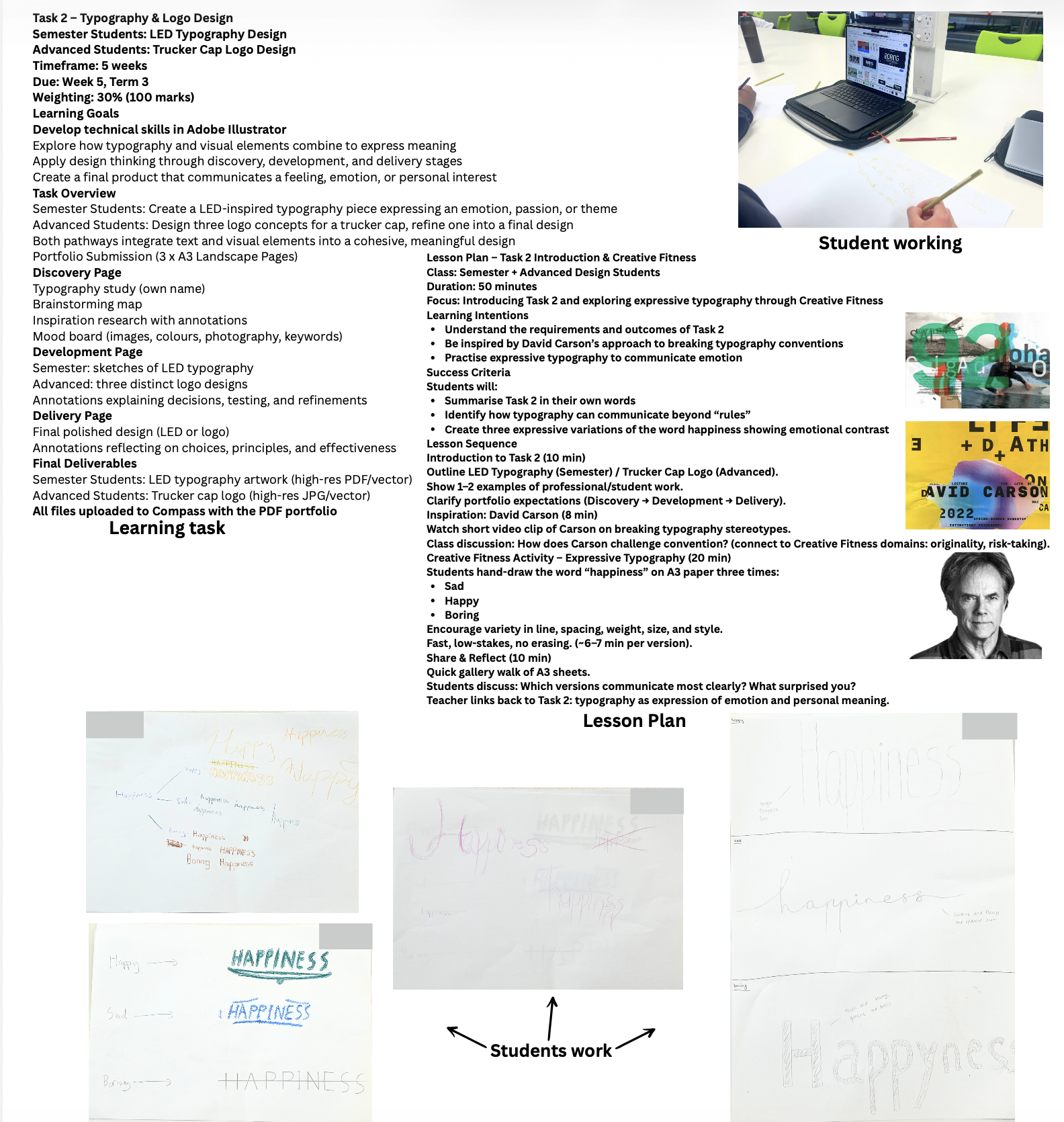

2.1 – Develop teaching activities that incorporate differentiated strategies to engage all learners

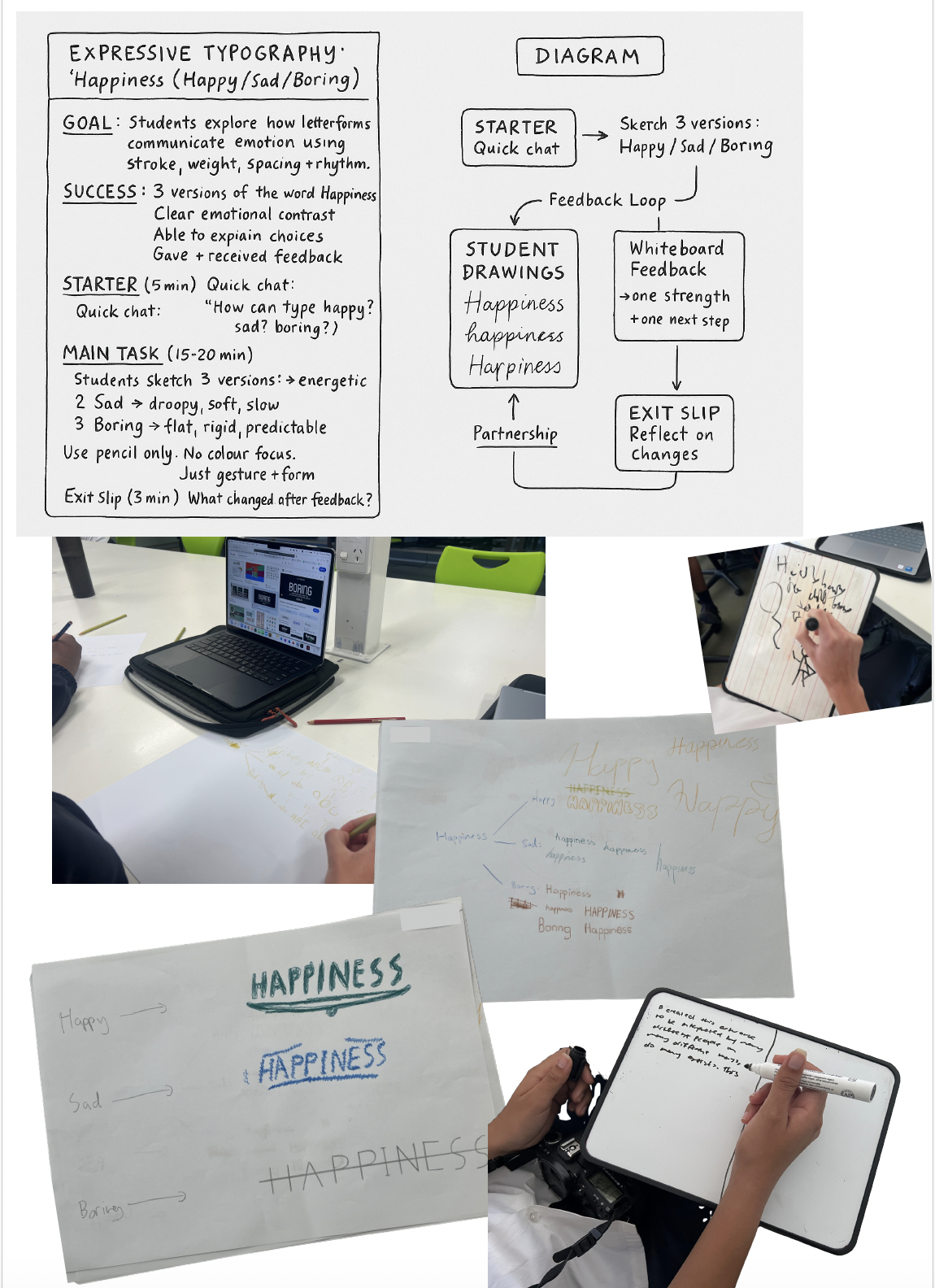

When introducing Task 2 (LED Typography for semester students / Trucker Cap Logo for advanced students), I built in differentiation at both the task design and activity level. The two versions of the brief provided an appropriate challenge for each pathway, while still focusing on shared skills in typography, design thinking, and Adobe Illustrator. In the launch lesson, students first engaged with David Carson’s talk on breaking typographic stereotypes, which primed them to think critically about convention and risk-taking. To make this immediately practical, we then used a Creative Fitness activity: students hand-drew the word happiness three times on A3 paper—once sad, once happy, once boring. This fast, low-stakes task allowed students to explore how typography communicates emotion through weight, spacing, and form. Differentiation happened naturally in this activity. Risk-takers pushed boundaries with dramatic distortions, while more cautious students found expression through subtle adjustments. The variety of responses (examples shown here) demonstrated that every learner could enter the task at their own level of confidence, while still being stretched to experiment beyond their comfort zone. This approach ensured all students—whether advanced or semester-long—were actively engaged and able to see personal relevance in the work.

3.3 – Include a range of teaching strategies

Across the Creative Fitness initiative, I deliberately integrated a wide repertoire of teaching strategies to make creativity visible, explicit, and actionable for all learners. Each of the Eleven Modal Domains is paired with a targeted micro-task designed to isolate a specific cognitive or creative behaviour. These micro-tasks draw on modelling, worked examples, analogical reasoning, guided practice, collaborative construction, rapid prototyping, and timed creative constraints to stimulate diverse modes of thinking. By structuring each activity through an “I do, we do, you do” release, I ensured students had clear demonstrations, shared experimentation, and independent application. Tasks were intentionally varied—visual, verbal, embodied, collaborative, reflective—to accommodate different learning preferences and provide multiple entry points for engagement. This variation helped students recognise creativity as a process rather than a product, giving them frequent opportunities to practise divergent, convergent, and metacognitive strategies in quick, low-stakes cycles. Taken together, these strategies created a sustained culture of creative participation: students generated ideas rapidly, iterated openly, collaborated fluidly, and articulated their thinking with increasing confidence. The variety of approaches enabled them to develop not only their creative skills, but the learning behaviours—risk-taking, resilience, discipline, empathy—that underpin meaningful creative growth.

5.1 Assess student learning

This lesson demonstrates AITSL Standard 5.1 through a cycle of assessment-for-learning that was immediate, visible, and actionable. Students were asked to express three distinct emotional tones—happy, sad, and boring—using only typography. Because the task relies on subtle decisions about line, rhythm, spacing, and gesture, it allowed me to assess their understanding in real time and provide ongoing feedback as they worked. During the sketching phase, I circulated and offered short, targeted verbal prompts tailored to each student’s process: “try exaggerating the bounce,” “slow the movement here,” “your sad version still has too much energy,” “remove contrast and see what happens.” These micro-interventions guided students toward deeper awareness of how typographic decisions communicate emotion. They were able to apply the feedback immediately, adjusting stroke weight, altering spacing, or exploring alternative gestures. The photos capturing students’ multiple pencil iterations reveal this live, formative assessment in action — ideas evolving, errors crossed out, new directions quickly explored. The peer feedback process strengthened this assessment loop. Using small whiteboards, students evaluated each other’s work by writing one strength and one next step. The images show students actively translating their observations into concise, constructive language: suggestions about spacing, rhythm, thick vs. thin strokes, emotional expressiveness, or conceptual ideas such as “letting go of innocence.” Because the feedback was written, not just spoken, it had to be clear and specific, modelling the kind of precision required in design critique. Students then returned to their sketches and made revisions based on this peer input, demonstrating evidence of learning through immediate refinement rather than delayed correction. This workflow illustrates AITSL 5.1: learning was continuously assessed through observation, dialogue, peer critique, and iterative making. Feedback was timely and directly connected to the learning intention — improving the clarity and emotional communication of typographic choices. Students acted on feedback instantly, not in a later lesson, which made the assessment authentic and formative. Their final sketches, annotations, and exit reflections all show visible improvement, deeper thinking, and strengthened understanding of how type communicates meaning. This lesson not only assessed what students could do, but actively moved their learning forward through cycles of responsive, collaborative feedback.

3.5 Effective Classroom Communication Supporting Participation & Agency

Across this Creative Fitness Sprint, communication is used deliberately to activate student agency and ensure every learner can participate with confidence. The lesson opens with a clear, invitational prompt that reframes complexity into accessible creative action, using simple questions and visual modelling to spark curiosity and remove the fear of being “wrong.” Students enter the task with concise, structured instructions—three divergent concepts, no erasing, ideas before polish—enabling them to direct their own workflow without relying on constant teacher approval. Throughout the sprint, students engage in peer-to-peer critique using the WWW/EBI language modelled by the teacher, which standardises feedback expectations and empowers students to influence and refine each other’s designs. As images show students sketching, exchanging pages, and annotating their thought processes, communication operates as a shared tool rather than a top-down directive: sentence starters, micro-cues, and reflective prompts all guide students toward deeper thinking while preserving their autonomy. Teacher circulation supports this by offering brief, precise nudges—never taking ownership of the idea but sharpening the student’s direction. The cumulative effect, visible in the full sequence of images, is a classroom where communication structures create momentum, clarity, and psychological safety. Students participate actively, make bold creative decisions, and reflect on how their peers’ insights shaped their outcomes. This demonstrates the effective use of communication to build a learning environment where agency is not only encouraged but practised.

Reference List:

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context: Update to the social psychology of creativity. Westview Press.

Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2009). Teaching for creativity with disciplined improvisation. In R. A. Beghetto & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), Nurturing creativity in the classroom (pp. 73–93). Cambridge University Press.

Glassman, G. (2002). What is fitness? CrossFit Journal, (10), 1–11.

https://journal.crossfit.com/article/what-is-fitness

Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond big and little: The four c model of creativity. Review of General Psychology, 13(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013688

Ritchhart, R. (2015). Creating cultures of thinking: The 8 forces we must master to truly transform our schools. Jossey-Bass.

Robinson, K. (2009). The Element: How finding your passion changes everything. Penguin Books.

Runco, M. A. (2014). Creativity: Theories and themes: Research, development, and practice (2nd ed.). Academic Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (2004). Imagination and creativity in childhood. Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 42(1), 7–97. https://doi.org/10.2753/RPO1061-040542017

6.2 Engaging in Professional Learning to Strengthen and Evolve Practice

This collection of images documents two professional development sessions I designed and delivered as part of my ongoing commitment to meaningful, research-informed professional learning. The first session, presented at ATOM WA, focused on mapping the ATAR Design course backward into the middle-school years. I used Creative Fitness not only as the structural framework for the workshop itself but also as a pedagogical model to show how design thinking can be embedded authentically within tasks from Years 7–10. Participants engaged in hands-on creative activities, examined annotated student work, and explored how Creative Fitness amplifies conceptual development and agency within design education.

The second session took place within my learning area at Perth Modern School, where I introduced colleagues to the Creative Fitness framework in the context of our full 7–12 Design pathway. Here, I clarified how our design thinking processes operate across year levels, demonstrated how Creative Fitness shapes curriculum decisions, and modelled how it supports consistent, vertically aligned skill development. The workshop materials—slides, task sequences, exemplars, and collaborative sketches—reflect an evidence-based approach that draws on current research, professional standards, and iterative refinement of my own practice.

Across both PD experiences, I engaged deeply in professional dialogue, contributed leadership within the wider teaching community, and used feedback and reflection to further improve my programs. These sessions exemplify my commitment to expanding professional learning opportunities for colleagues while continually strengthening my own teaching through shared inquiry and contemporary pedagogical thinking.

Reference List:

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context: Update to the social psychology of creativity. Westview Press.

Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2009). Teaching for creativity with disciplined improvisation. In R. A. Beghetto & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), Nurturing creativity in the classroom (pp. 73–93). Cambridge University Press.

Glassman, G. (2002). What is fitness? CrossFit Journal, (10), 1–11.

https://journal.crossfit.com/article/what-is-fitness

Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond big and little: The four c model of creativity. Review of General Psychology, 13(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013688

Ritchhart, R. (2015). Creating cultures of thinking: The 8 forces we must master to truly transform our schools. Jossey-Bass.

Robinson, K. (2009). The Element: How finding your passion changes everything. Penguin Books.

Runco, M. A. (2014). Creativity: Theories and themes: Research, development, and practice (2nd ed.). Academic Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (2004). Imagination and creativity in childhood. Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 42(1), 7–97. https://doi.org/10.2753/RPO1061-040542017