Developing Executive Functions through Project-Based Learning

AITSL Focus Areas: Differentiate teaching to meet specific learning needs (1.5) Apply professional learning and improve student learning (6.4) Strategies to support full participation of students with disability (1.6) Manage challenging behaviour (4.3)

Situation

In my role as a Photography and Design teacher at Perth Modern School, I work with high-achieving students who often excel in academic knowledge but may lack key executive functioning skills such as planning, time management, impulse control, and metacognitive awareness. These skills are especially important in creative disciplines like design, where open-ended, long-term projects require independent decision-making, collaboration, and sustained focus.

My goal was to embed the explicit development of executive functions within project-based learning (PBL), shifting away from isolated instruction and toward authentic contexts. I also drew upon my Montessori training to support a more student-centred, flexible classroom model.

Action

1. Course-Level Structure – Year 7 Photography & Design

The Year 7 Photography & Design course is intentionally sequenced to support executive function growth across multiple domains. Each phase of the design process aligns with an executive skill, as illustrated below:

Course Component Executive Functions Developed Aligned Habit of Mind Mood Board CreationPlanning, Organisation, Cognitive Flexibility Creating, Imagining, Innovating Prototype Sketching Task Initiation, Working Memory, Self-Monitoring Managing Impulsivity Final Design (Illustrator)Time Management, Attention Control, Persistence Persisting Portfolio Development Goal-Directed Persistence, Metacognition Thinking about Thinking Studio Photography Planning, Emotional Regulation Managing Impulsivity + Striving for Accuracy Photoshop Editing Attention to Detail, Inhibitory Control Striving for Accuracy Reflective Writing Metacognition, Perspective-Taking Thinking about Thinking

These links are made explicit through student modelling, classroom posters, and shared vocabulary.

2. Strategy: Small Group Teaching (Montessori-Informed)

Adapting a Montessori approach, I invited students to form their own working groups based on natural collaboration preferences. This decentralised model fostered peer accountability and mutual support. Within these groups, I delivered feedback collectively, using group dynamics to reinforce learning while still preserving moments for individual feedback.

This strategy helped normalize collaborative planning, encouraged distributed responsibility, and gave students a sense of autonomy over their workflow—critical for ownership and self-regulation.

3. Strategy: Scaffolded Task Submissions

To help students with project planning and self-monitoring, I prototyped breaking larger assessments into more minor submission points (e.g., Part 1: Mood board, Part 2: Prototype, Part 3: Final). While this initially supported executive load and sequencing, I noticed reduced ownership among some students and task fatigue due to overlapping deadlines.

This reflection has led me to refine how and when scaffolds are offered—prioritising flexible pacing and student input over rigid checkpoints.

4. Strategy: Whiteboard Collaboration (Nottingham-Inspired)

I regularly use individual mini whiteboards for non-pressured formative assessment. Students answer prompts silently, share responses in small groups, and then we transition to whole-class discussions.

As James Nottingham highlights, slowing the response cycle down encourages deeper thinking. This practice reduces performance anxiety and allows students to develop metacognition in a collaborative and playful format.

5. Case History: “SATRSGFD” – Building Support Structures

One of my core beliefs is that teachers must be willing to spend 80% of their energy on 20% of their students. “SATRSGFD” (de-identified name) presented with challenges in sustained attention and planning. Regular classroom support was paired with lunch-time mini sessions, where we worked on breaking down tasks and managing distractions. I maintained close communication with the student’s parent, offering insights into school routines and strategies for home.

Over time, this student gained confidence in initiating tasks, using visual planners, and completing portfolio checkpoints with fewer prompts. Our ongoing dialogue with their parent helped reinforce executive strategies across environments.

Outcome

Across multiple cohorts and over several years, I’ve observed clear improvements in students’ ability to manage multi-step projects independently. In particular:

Increased self-initiation of project milestones

Improved time management, visible through timely submissions

Stronger reflection and feedback engagement, seen in portfolio entries and classroom discussions

Peer support cultures are emerging organically, especially in small-group feedback and studio setups

Students have explicitly used terms like "planning my time better," "getting started early," and "knowing how I think" in their reflections—language that signals internalisation of executive function awareness.

This developmental arc echoes research from Harvard’s Centre on the Developing Child (2011), which stresses the role of structured, meaningful tasks in developing executive capacity. It also aligns with Habits of Mind (Costa & Kallick, 2000), particularly the cultivation of dispositions like “Persisting,” “Managing Impulsivity,” and “Thinking about Thinking,” all of which underpin strong executive function.

Ultimately, my practice demonstrates that when project-based learning is paired with intentional strategy and relational teaching, it becomes a powerful engine not only for academic achievement but also for cognitive empowerment.

References

Centre on the Developing Child at Harvard University. (2011). Building the Brain’s “Air Traffic Control” System: How Early Experiences Shape the Development of Executive Function. https://developingchild.harvard.edu

Costa, A. L., & Kallick, B. (2000). Habits of Mind: A Developmental Series. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Dawson, P., & Guare, R. (2009). Smart but Scattered: The Revolutionary “Executive Skills” Approach to Helping Kids Reach Their Potential. New York: The Guilford Press.

Education Endowment Foundation (EEF). (2021). Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning. Retrieved from https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. London: Routledge.

Nottingham, J. (2017). The Learning Challenge: How to Guide Your Students Through the Learning Pit to Achieve Deeper Understanding. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Robinson, K. (2009). The Element: How Finding Your Passion Changes Everything. New York: Viking.

Annotated Evidence

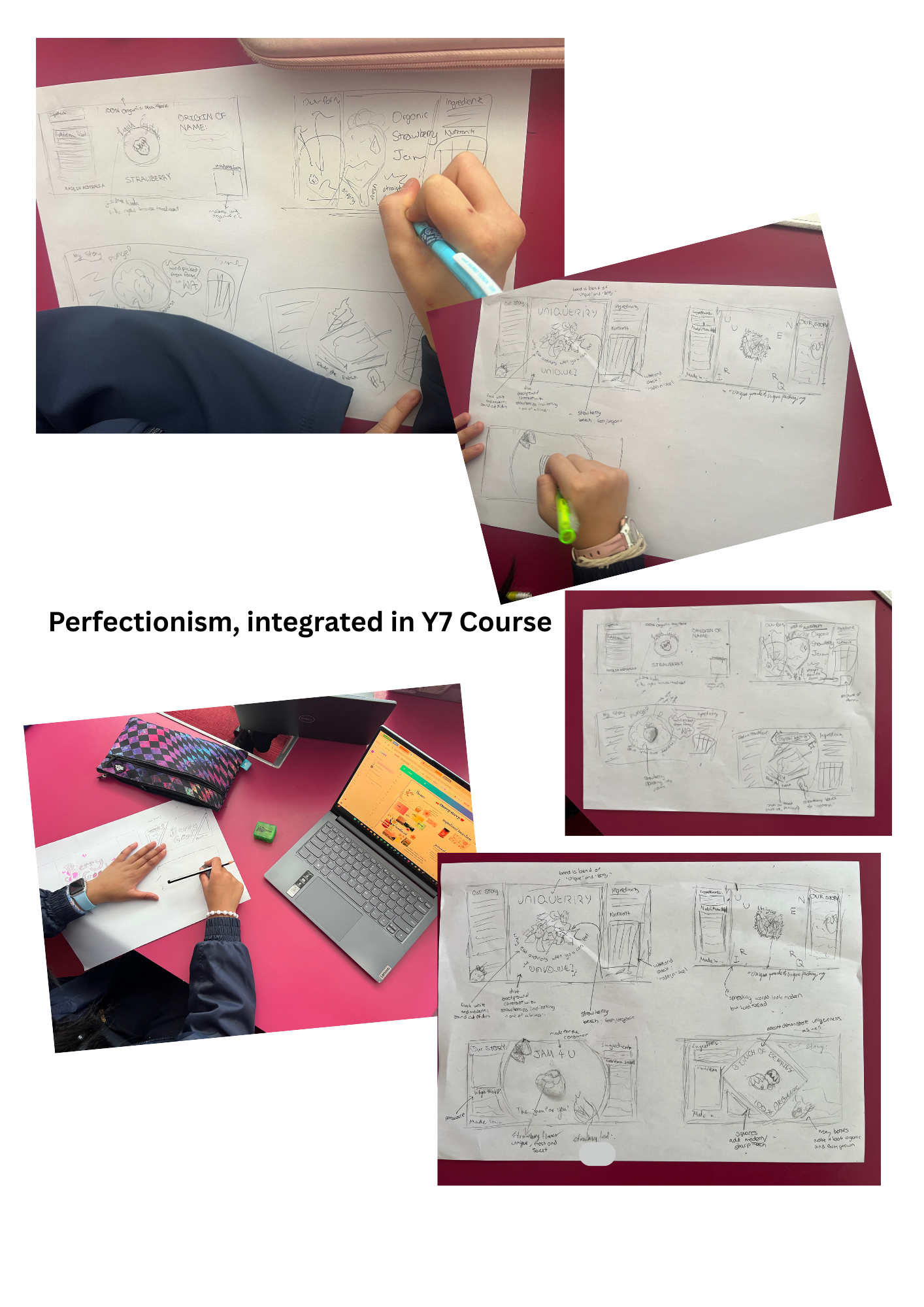

1.5 Differentiation Through the Creative Fitness Ideation Sprint

The images show the Creative Fitness ideation sprint that opens my Year 7 Photography & Design course. This single 30-minute activity is one of the most powerful differentiation tools I use, because it reveals how each student thinks before the course begins to shape them.

Students produce one initial food-label concept, then three rapid, non-complementary iterations. The time limit disrupts perfectionism—a common barrier for high-achieving students—and invites cognitive flexibility. Because the drawings are intentionally low-fidelity, every student can participate without fear of “getting it wrong.” Some generate symbolic ideas, others narrative scenes, others structured layouts; the variation in the images demonstrates students moving through the task in ways aligned to their strengths, preferences, and executive functioning profiles.

Peer feedback through the WWW/EBI protocol further differentiates the experience. Students receive comments that match their cognitive stance: risk-takers are nudged toward refinement; perfectionistic thinkers are encouraged to loosen up; quiet conceptual thinkers are validated for depth; fast executors are urged to slow down and reflect. The designs become diagnostic tools, showing me who needs support with planning, who needs permission to take risks, and who needs scaffolds to manage impulsivity or over-control.

By explicitly teaching that perfectionism is both a strength and a constraint, this activity creates psychological safety for all learners. Students learn that early ideas are meant to be rough, messy, and generative—an essential foundation in design thinking. In doing so, the task differentiates not by offering different work but by offering multiple cognitive entry points within the same task.

This Creative Fitness exercise enables me to tailor instruction for the remainder of the course. It surfaces executive-function needs, creative tendencies, pacing preferences, and confidence levels within minutes. Students take their learning where they need it to go, and I adjust the environment around their emerging profiles.

In this way, the ideation sprint is a deliberately designed, low-stakes, high-diagnostic activity that meets AITSL 1.5 by allowing every student to engage meaningfully according to who they are, not just what they can produce.

1.6 – Supporting Full Participation of Students with Disability

The images illustrate how I embed executive-function scaffolds into the Year 7 Photography & Design course to support students—including those with ADHD, ASD traits, or other learning needs—to participate fully and successfully in open-ended creative tasks. By breaking complex design processes into low-stakes sketching rounds, visual planners, and iterative drafting, I reduce cognitive load and provide multiple entry points for students who require additional structure to access the curriculum. My modelling of imperfection, the explicit teaching of how to start, and the repeated reframing of perfectionism directly address common barriers experienced by neurodiverse learners, supporting them to remain engaged, regulated, and confident in their capacity to contribute meaningfully. These practices align with policy expectations for inclusive participation, ensuring that students with disability can demonstrate learning through alternative pathways such as drawing, brainstorming, or verbal explanation. In doing so, I design and implement teaching activities that meet legislative and school requirements for equitable access while strengthening students’ sense of agency and belonging within a high-performance environment.

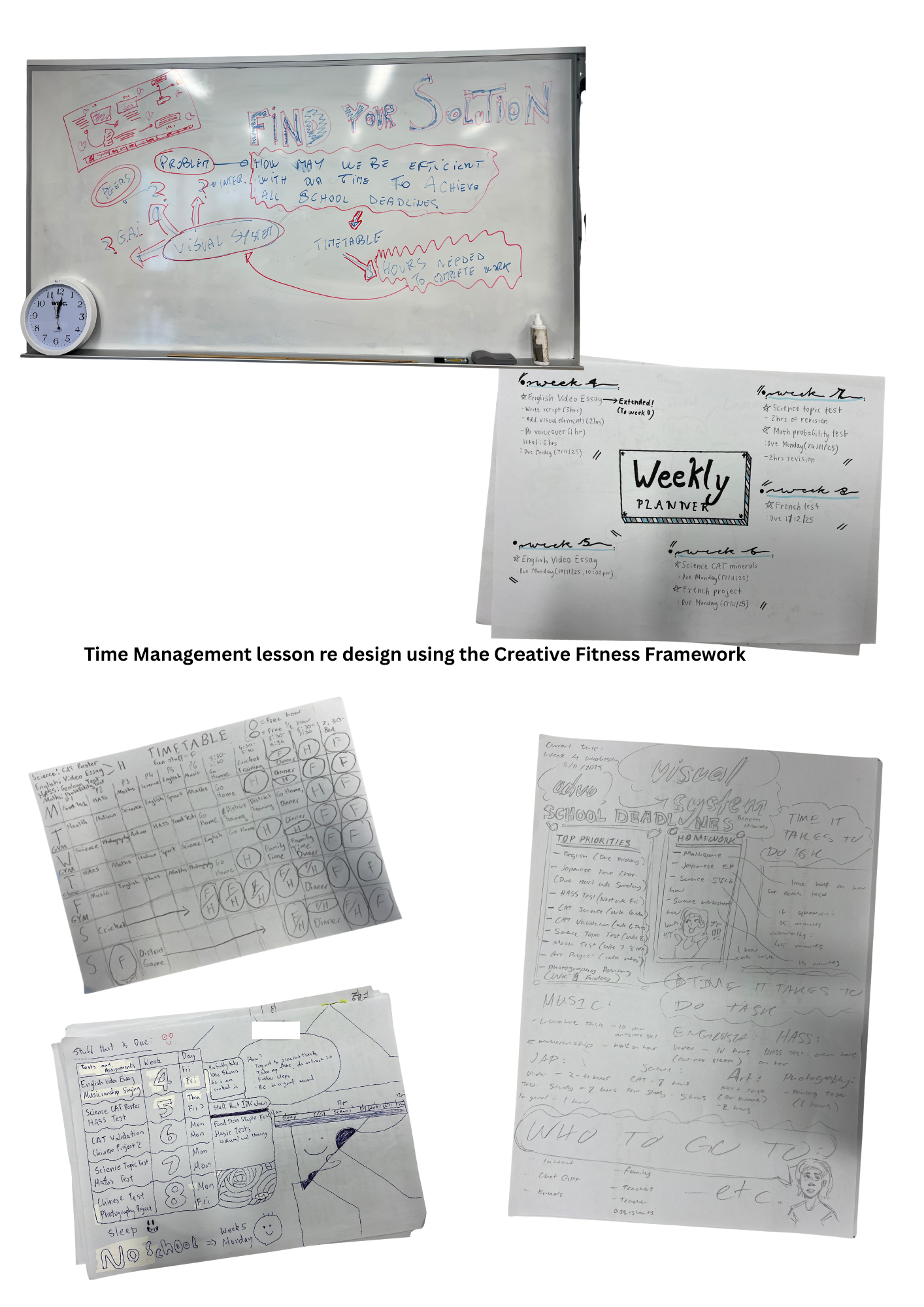

6.4 – Image Narrative (Time-Management Lesson Using the Creative Fitness Framework)

The images capture the final phase of a time-management learning sequence undertaken by my Year 8 Advocacy class after an external professional learning session delivered by a university volunteer. Building on that workshop, I redesigned the closing activity using the Creative Fitness Framework so that students could create their own time-management systems rather than completing standardised worksheets.

The first image shows the whiteboard design challenge that framed the entire lesson. Together, we mapped the problem: How might we be more efficient with our time to achieve school deadlines? Students identified the pressures they face, the hours available each week, and the reality of workload across subjects. This visual scaffold positioned time management as a shared design problem — something they could break apart, analyse, and reconstruct.

The next set of images shows students’ individual weekly planners, each uniquely structured. These hand-drawn systems reveal how students visualised their school week: some created linear calendars; others chose quadrant-based priority maps; a few developed hybrid grids that tracked homework load, test preparation, or extracurricular commitments. Each planner reflects personal interpretation — the student’s own understanding of how their time flows and what structures support them best.

Another image shows a highly detailed task-breakdown system, where a student itemised deadlines across subjects and built a personalised visual dashboard combining hours needed, task importance, and emotional load. This demonstrates metacognitive awareness and the ability to translate abstract executive-function advice into a working model.

The remaining student samples show creative visual systems—mind-maps, lists, icons, and illustrated planners. The diversity across these artefacts indicates that students were not following a template; instead, they were designing systems grounded in their own strengths, pressures, and preferences. This is exactly why the Creative Fitness approach was used: it allows students to convert a general skill (time management) into a personal tool they can actually use.

Collectively, the images show students applying external professional learning through a deeply individualised, design-thinking lens. Their planners, diagrams, and sketches demonstrate ownership, self-regulation, and the development of executive functioning skills — all linked back to the PL I received and then transformed into improved student learning.

4.3 – Managing Challenging Behaviour

The images show a time-management redesign lesson created using my Creative Fitness framework, in which students developed personalised weekly planners, visual systems, and timetables. This activity was delivered in my Y8 Advocacy class—a group identified by the school as having some of the most challenging behaviours. Over multiple years, I have applied a consistent suite of relational and instructional strategies to support these students, including individual reflection journals completed with me during lunch or recess, ongoing check-ins, and Montessori-informed practices such as workspace choice, movement, and hands-on problem-solving.

By designing the lesson around an authentic problem—How do we manage our time to meet school deadlines?—the task removed the oppositional triggers that commonly drive behavioural escalation. Students were able to work collaboratively at the back table, share ideas, and take genuine ownership of their learning. The open-ended, visual nature of the task enabled entry points for all students, particularly those who struggle with traditional written tasks, and significantly reduced resistance, avoidance, and off-task behaviours.

These images demonstrate how I manage challenging behaviour by establishing clear expectations, providing structured yet flexible learning pathways, and creating meaningful tasks that allow students to experience competence and agency. Through ongoing individual mentoring, reflective routines, and responsive task design, I maintain a classroom environment where even our most behaviourally complex students can engage respectfully, productively, and with increasing self-regulation—meeting AITSL 4.3 at the proficient level.