Feedback is a Skill: Deepening Design Thinking through Feedback Literacy

AITSL Focus Areas: Provide Feedback to students on their learning (5.2)

“If you give feedback after the task is completed, it’s too late. The learning moment has passed.”

— James Nottingham, Teach Brilliantly (2023)

Situation

As a teacher of Design, I work at the intersection of creativity, iteration, and inquiry. Design Thinking cannot flourish without feedback: critique and revision are fundamental to progress. But I recognised a persistent problem in my classroom: students didn’t know how to use feedback meaningfully. It was seen as correction, not as guidance for growth.

My journey into reframing feedback began with a whole-staff professional learning day led by James Nottingham at John Curtin College of the Arts. His statement about the importance of timing in feedback radically shifted my perspective. Feedback needed to happen while the work was still live—not after submission. This insight sparked a shift in both my classroom practice and my leadership.

Action

Following Nottingham’s session, I led a small group PL at my school, exploring his book Teach Brilliantly with colleagues. We examined how feedback works best when embedded into the learning process, and what it means to explicitly teach feedback as a student skill.

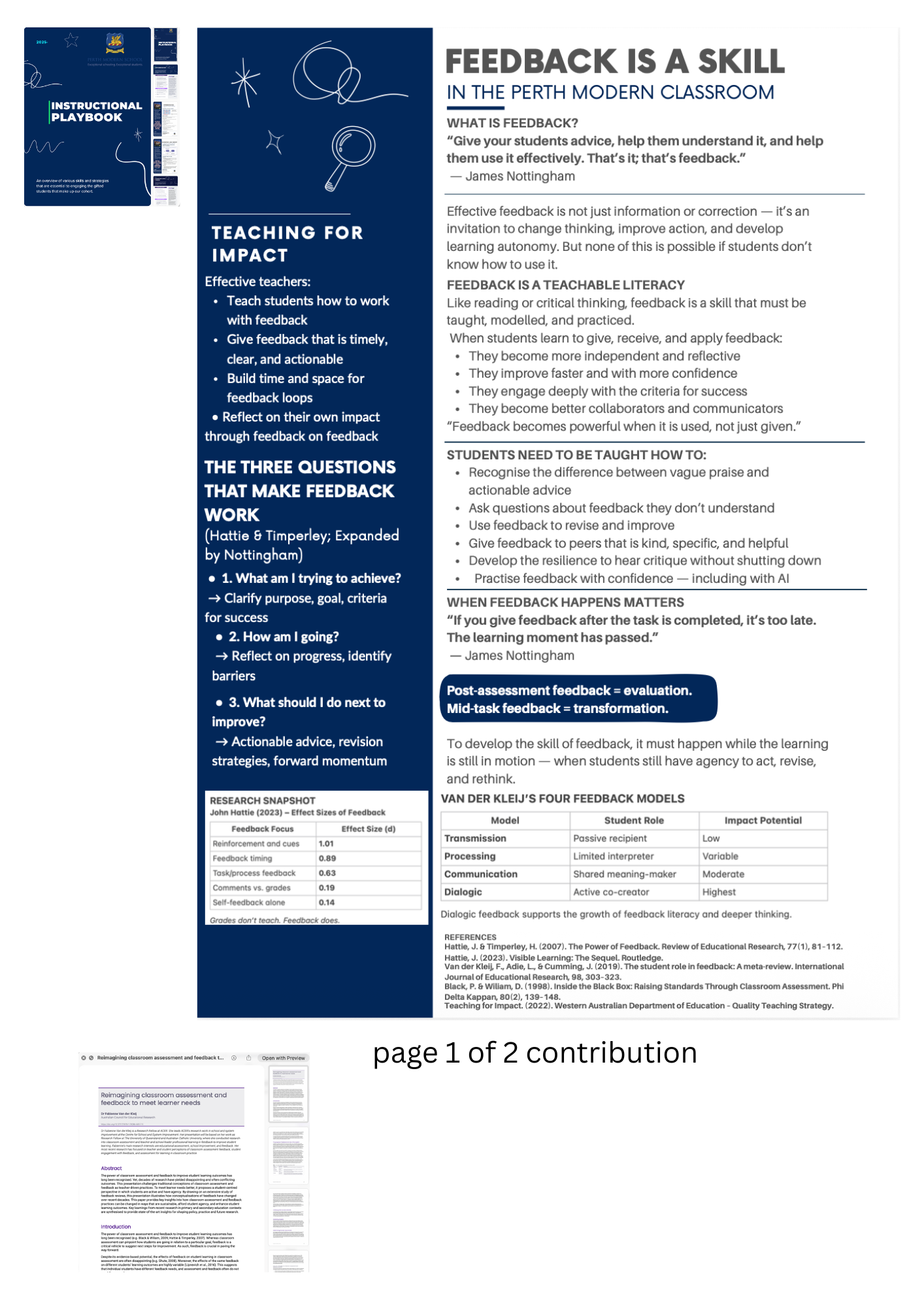

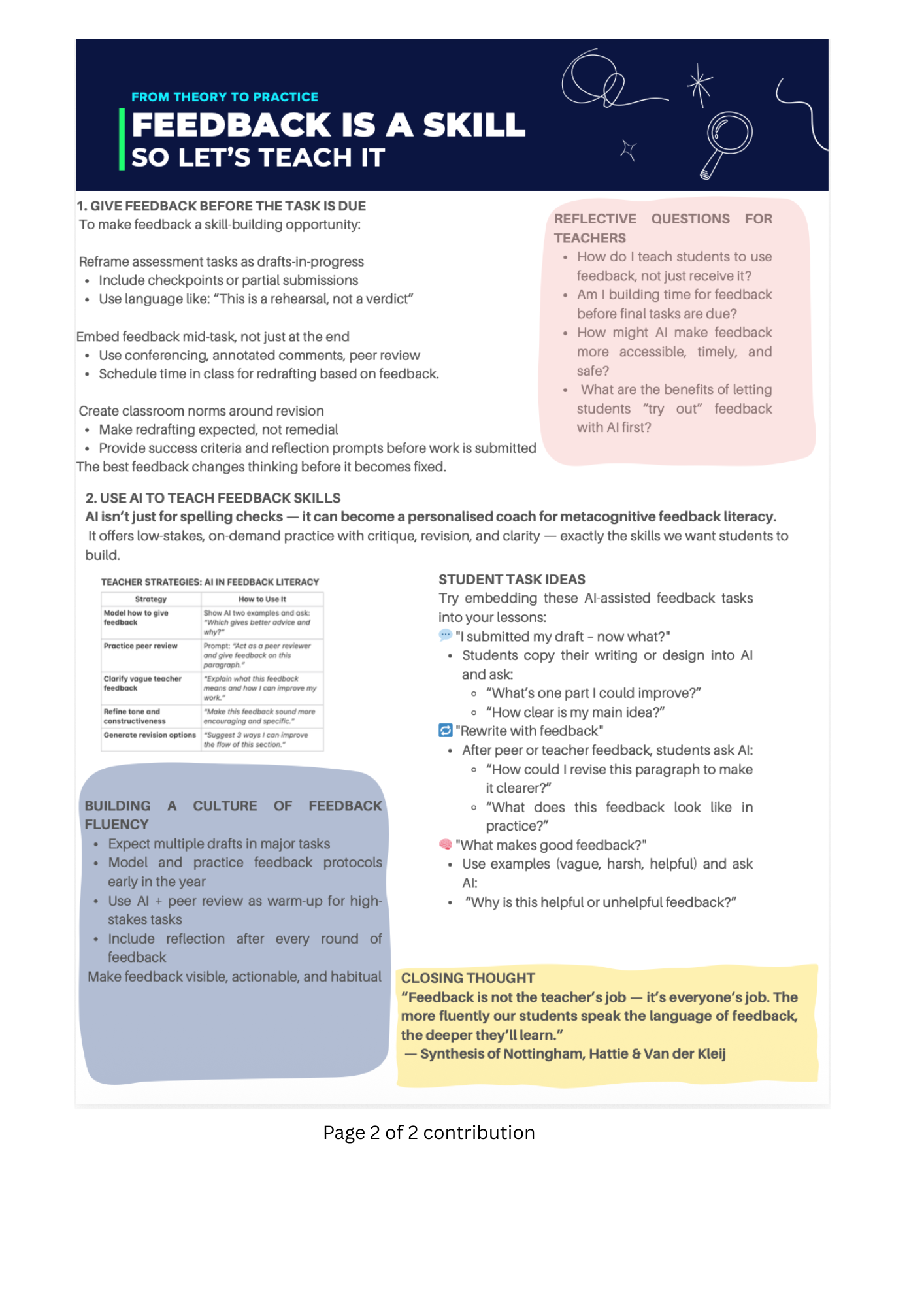

Soon after, I was invited by a colleague to contribute to our Instructional Playbook initiative. I proposed and co-authored the double-page spread “Feedback is a Skill.” Page one captured key theory (Hattie, Nottingham, Van der Kleij), and page two translated that theory into practice—including ways to use AI as a feedback literacy tool.

I overhauled feedback practices within my major design tasks. I introduced mid-task checkpoints where feedback could be given before final submission. I reframed assessments as drafts-in-progress and embedded peer review and AI-supported feedback loops, teaching students to use ChatGPT to clarify teacher comments, generate revision suggestions, and reflect on vague or confusing peer feedback.

In line with Nottingham’s view that feedback is most effective during learning, I now distinguish between feedback and post-task commentary. I no longer label comments after submission as “feedback.” Instead, I use terms like Teacher Comment and Performance Review. This clarifies the intent—evaluation, not transformation—and is supported by detailed rubrics co-developed with students and moderated marking with colleagues for fairness and consistency.

Outcome

By introducing mid-task checkpoints, reframing assessment tasks as drafts-in-progress, embedding peer and AI-supported review processes, and replacing post-task “feedback” with Teacher Comment and Performance Review, I have cultivated a culture of continuous dialogue around learning. I am now working with students to establish a genuine community of practice where feedback is expected, understood, and exchanged as a normal part of our classroom environment. This evolving culture supports feedback as a shared responsibility—between teacher and student, and between peers—where critique and reflection are seen not as isolated interventions, but as an integral part of deep learning in design.

References

Nottingham, J. (2023). Teach Brilliantly: Small Shifts That Lead to Big Gains in Student Learning. Routledge.

Hattie, J. & Timperley, H. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112.

Hattie, J. (2023). Visible Learning: The Sequel. Routledge.

Van der Kleij, F., Adie, L., & Cumming, J. (2019). The student role in feedback: A meta-review. International Journal of Educational Research, 98, 303–323.

Black, P. & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the Black Box: Raising Standards Through Classroom Assessment. Phi Delta Kappan.

Teaching for Impact. (2022). Western Australian Department of Education.

Annotated Evidence

5.2 Modelling and Embedding Effective Feedback Practices Across Classroom and School

The images in this evidence set capture the evolution and enactment of my feedback practice at Perth Modern School. The two-page spread I authored for our Instructional Playbook—“Feedback Is a Skill in the Perth Modern Classroom”—reflects the consolidation of theoretical learning (Hattie, Nottingham, Van der Kleij) into a practical framework for teachers. Page one distils the research: the timing of feedback, the characteristics of actionable advice, and the role of students as active co-creators in the feedback process. Page two translates these ideas into classroom practice, offering concrete strategies such as mid-task conferences, peer review protocols, revision checkpoints, and the deliberate use of AI as a metacognitive support tool.

The images of academic articles, Nottingham’s models, and the research effect-size table demonstrate the depth of professional learning that informed my contribution. They show how I drew directly from evidence-based work to establish a shared definition of feedback and propose actionable structures for teachers school-wide.

The emails from my Head of Learning Area and Associate Principal further contextualise the impact of this contribution. They acknowledge the clarity, usefulness, and influence of my pages—recognising them as a cornerstone of our developing Instructional Playbook and noting their relevance for leadership discussions at the Directors’ Meeting. These communications demonstrate how my work supported colleagues in applying timely, effective, and appropriate feedback strategies, directly aligning with the highly accomplished descriptor of AITSL 5.2.

The images also show how these ideas are enacted in my classroom. My feedback practices operate through communal table conferencing, where I move continuously among students, offering mid-task feedback aloud so peers can listen, learn the language of critique, and improve their own work through observation. This structure—visible across the student portfolio drafts, storyboard sketches, and digital animation works-in-progress—ensures feedback is not private correction but a shared, iterative learning tool. Students practise giving and receiving critique, asking clarifying questions, and applying revision strategies in real time.

Finally, the explicit inclusion of AI-driven feedback loops, shown in the playbook examples, reflects my commitment to equipping students with modern feedback literacies. Students use AI to clarify teacher comments, identify next steps, rewrite sections for clarity, and explore alternative solutions—expanding their capacity to act on feedback independently.

Together, the evidence demonstrates a coherent, research-informed approach to feedback that:

• prioritises mid-task, actionable guidance;

• builds student skill and confidence in using feedback;

• normalises revision as integral to learning; and

• supports colleagues in strengthening their own feedback practice.

This work exemplifies AITSL 5.2 through its explicit focus on feedback as a teachable skill, embedded habit, and shared responsibility across the classroom and school.