Co-Designing Learning: Student Voice in Year 10 Multimedia

AITSL Focus Areas: Support student participation (4.1), Physical, social and intellectual development and characteristics of students (1.1); Information and Communication Technology (ICT) (2.6); Establish challenging learning goals (3.1); Select and use resources (3.4); Use ICT safely, responsibly and ethically (4.5); Report on student achievement (5.5)

Situation

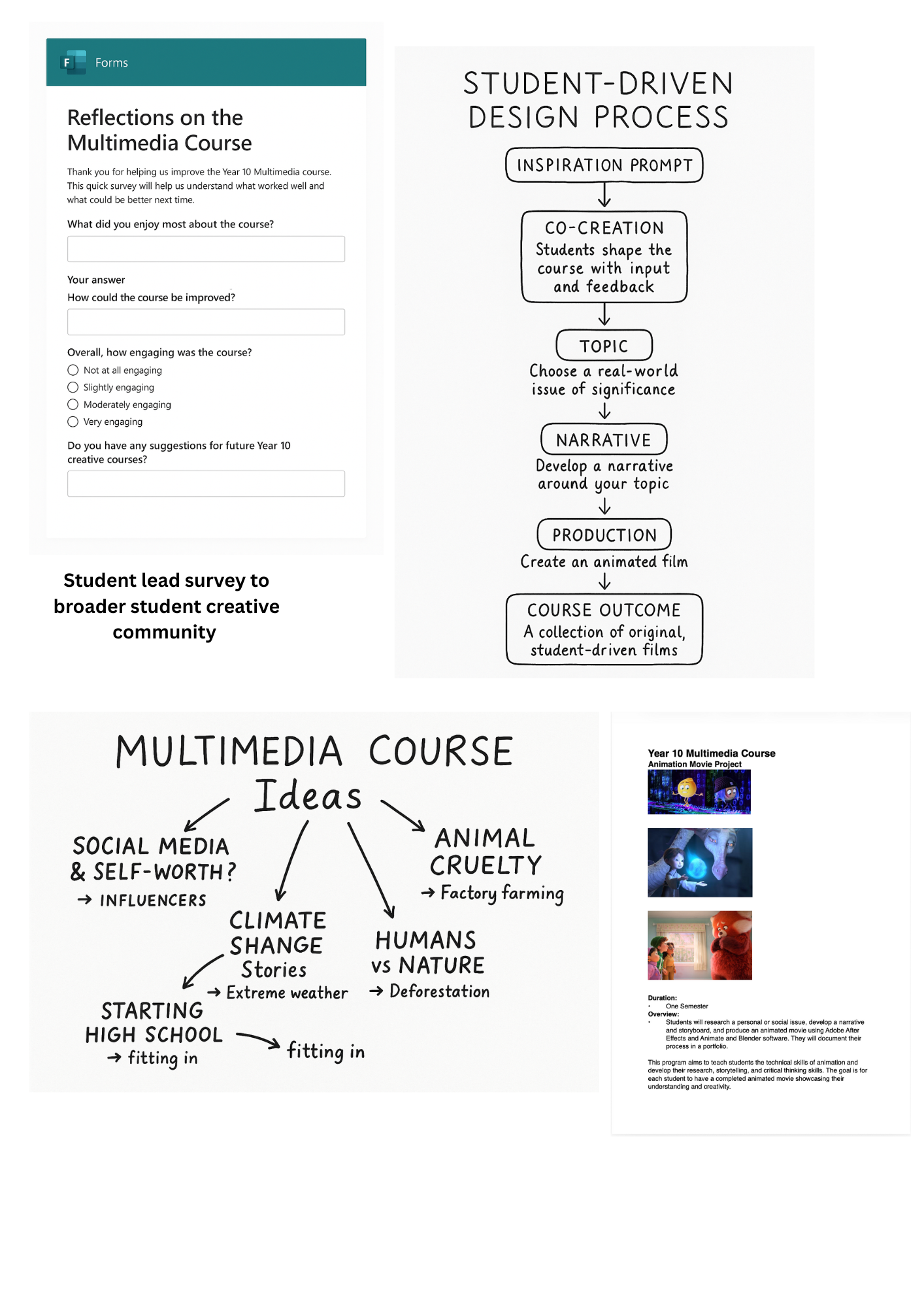

In my third year at Perth Modern School, I led a reimagining of the Year 10 Multimedia course to authentically embed student voice and agency not only in classroom activities, but in the design of the curriculum itself. Anchored in the Teaching for Impact framework, I understood student voice as more than just participation—it is about students influencing the direction, focus, and nature of their learning experiences.

Drawing on the work of Gonski et al. (2018) and Hattie (2009), I saw this as a chance to build a classroom where students were not passive consumers but creative partners—invested, autonomous, and reflective. The aim was to foster engagement, wellbeing, and achievement through shared ownership of learning.

Action

At the beginning of the semester, I presented students with an inspiration prompt—a broad provocation to explore personal or social issues they cared deeply about. From there, we co-designed the course together. Students chose their topics, shaped the narrative direction, and influenced how the technical and creative components would unfold. This foundational choice shaped the four task structure that followed:

Task 1 – Research and Narrative Development

Students chose a real-world issue of significance to them and built a narrative around it. Their ownership over the subject matter led to greater emotional investment and deeper learning.Task 2 – Storyboarding and Pre-production

Students visualised their narratives through moodboards, scripts, and character designs. They made stylistic and structural choices, which were discussed and supported in collaborative planning sessions.Task 3 – Production and Portfolio

Students brought their stories to life using Adobe After Effects, Blender, and Animate. Regular critique sessions and formative feedback loops enabled them to revise, self-evaluate, and reflect—hallmarks of self-regulated learning.Task 4 – Technical Development

A rolling series of software mini-tasks ran parallel to the main project. These were selected and adapted in consultation with students, based on emerging needs, interests, and challenges.

Responsive Teaching and Adaptation

Throughout the semester, I adjusted the course structure and support strategies based on student voice:

Task timeframes were adapted based on student progress and conceptual readiness.

I differentiated expectations and tutorials to meet individual needs and learning profiles.

When appropriate, tasks were modified to align better with cohort-specific goals and engagement patterns.

This adaptability was underpinned by continuous dialogue with students—modelling the Teaching for Impact principle of responsive co-design and demonstrating trust, transparency, and mutual respect.

Outcome

By semester’s end, students had produced a collection of powerful, original animated films that expressed their values, curiosities, and identities. The process yielded rich learning outcomes:

Students demonstrated heightened self-efficacy, confidently discussing their work and seeking critique.

The class operated as a collaborative design studio, where feedback and dialogue were routine and respectful.

Student reflections and portfolios showed deep growth in creative process, technical skill, and critical thinking.

For me, the experience deepened my belief that authentic student voice begins with co-design. Students were not just engaging with the curriculum—they were shaping it. This empowered them to become more autonomous, motivated learners and helped me evolve into a more responsive and adaptive educator.

This course embodied the Teaching for Impact call to action:

“When learning is co-constructed, students and teachers share a collective responsibility for progress and achievement.” (Teaching for Impact, p. 44)

Annotated Evidence

4.1 Supporting Student Participation Through Co-Designed Learning in Year 10 Multimedia

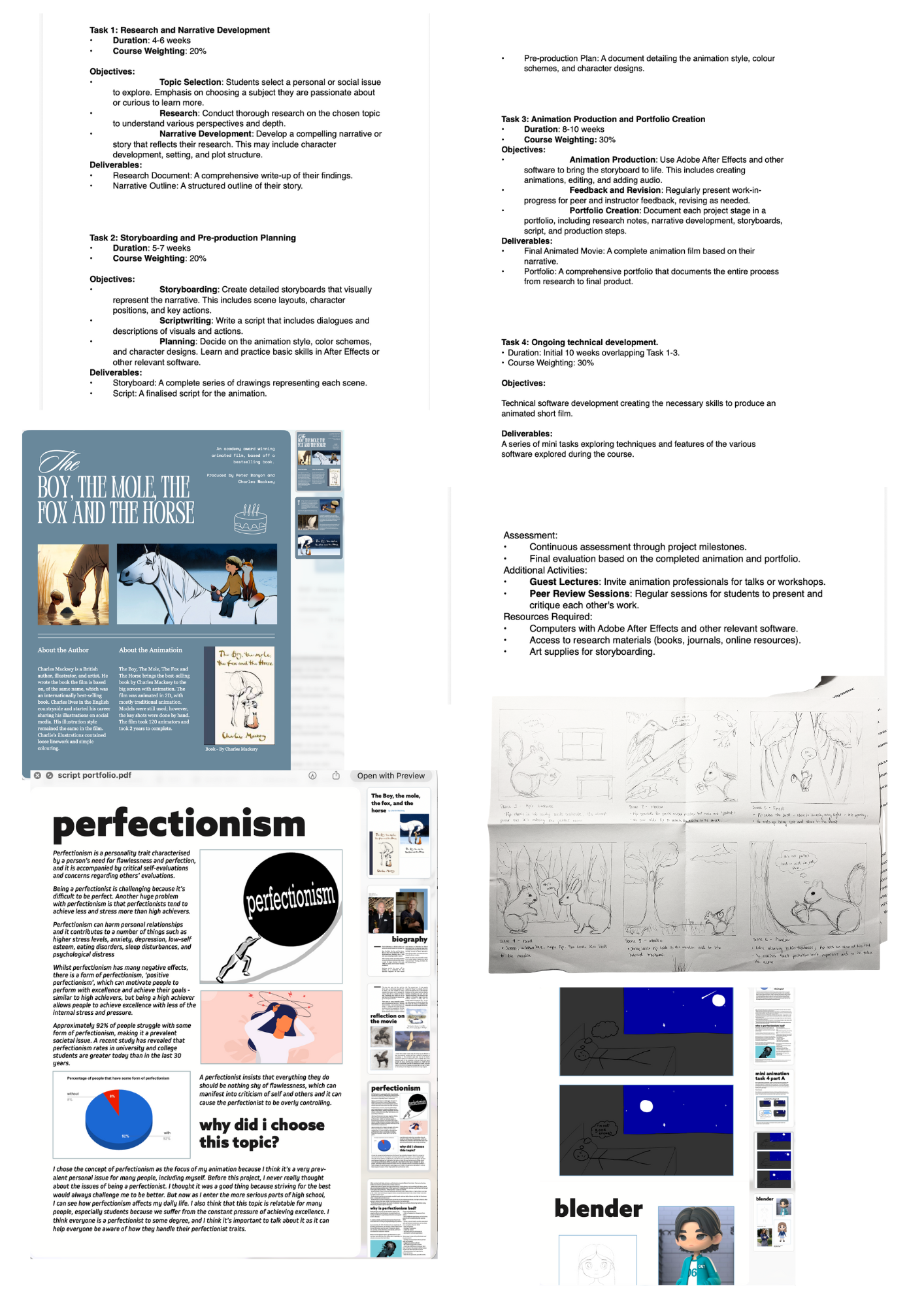

This evidence set demonstrates how the redesigned Year 10 Multimedia course was intentionally structured to support inclusive and meaningful student participation by embedding student voice directly into the design of the learning program. Rather than offering a predetermined sequence of content, I invited students into a co-design process from the outset—positioning them as partners who shape the direction, focus, and purpose of their learning. The student survey, brainstorming artefacts, topic mind maps, and narrative planning documents all illustrate how their interests, identities, and passions became the foundation of the course itself.

By allowing students to choose personal or social issues of significance, the course ensured that every learner could participate from a place of authenticity and relevance. The four-task structure—research, narrative development, storyboarding, production, and technical exploration—provided multiple entry points for diverse learners, enabling them to engage through strengths while also stretching their creative and technical capacities. Regular critique sessions, reflective journaling, and iterative feedback loops created a learning environment where students felt safe to experiment, revise, and take creative risks.

Throughout the semester, I adapted timelines, tutorials, and expectations in response to student feedback and emerging needs, demonstrating a responsive teaching approach that valued student voice as a legitimate driver of pedagogical decisions. This adaptability supported the participation of all students, including those with different learning profiles, confidence levels, or technical readiness. The classroom functioned as a collaborative design studio: inclusive interactions, shared problem-solving, and sustained dialogue anchored the learning culture.

By co-constructing the curriculum with students, I created a learning space that actively supported participation, agency, and engagement. This work exemplifies the intent of AITSL 4.1—establishing inclusive structures and interactions that empower all learners to contribute, take ownership, and thrive within classroom activities.

1.1 – Designing Learning Around Students’ Developmental Needs Through Co-Created Multimedia Projects

The redesign of the Year 10 Multimedia course was grounded in an explicit understanding of students’ physical, social, and intellectual development, which directly shaped how learning was structured and experienced. The student-led survey at the start of the semester provided developmental insight into students’ interests, sense of identity, social concerns, and engagement needs. These insights informed the co-design process outlined in the “Student-Driven Design Process” diagram, ensuring the course aligned with adolescents’ growing need for autonomy, relevance, and creative self-expression.

Across the planning and production phases shown in the images (topic brainstorming, narrative development, storyboarding, script writing, and Blender prototyping), I differentiated teaching strategies to match students’ developmental profiles. The open-choice topics supported emotional and social maturity; structured workflows supported cognitive development; and multimodal task design met the needs of diverse learners by allowing them to show understanding through visual, written, and technical forms. The documented task structure (Tasks 1–4) reflects this intentional scaffolding, ensuring challenge while supporting students’ developing executive functions.

By aligning curriculum design with what I know about adolescent development—autonomy-seeking, identity formation, peer-influenced motivation, and rapidly developing higher-order thinking—the course became developmentally responsive. The resulting student work evidences deep engagement, creative risk-taking, and growth in intellectual independence, demonstrating how understanding students’ developmental needs directly improved learning outcomes.

2.6 — Integrating ICT to Expand Creative Learning Opportunities in a Co-Designed Multimedia Course

The Year 10 Multimedia course shown in this evidence set demonstrates how ICT was central to both the design of the curriculum and the learning opportunities available to students. The images illustrate a workflow where students shift between digital storyboarding tools, Microsoft Forms surveys, Blender modelling, Adobe After Effects, digital research documents, and online portfolio drafting. These ICT platforms were intentionally selected to expand the creative and cognitive possibilities of the course, enabling students to work at an industry-aligned standard while shaping their own learning pathways.

ICT was not an add-on but the medium through which co-design occurred. The student survey shown provided real-time data that guided course restructuring and informed task pacing, technical instruction, and narrative focus. Students used digital environments to experiment, iterate, and revise at a depth not possible through analog methods alone. This aligns with the descriptor by showing how ICT made learning meaningful—students could visualise complex ideas, prototype rapidly, and build increasingly sophisticated animations across the semester.

Additionally, the evidence demonstrates how I model ICT pedagogical expertise and support colleagues. The co-designed course map, digital task booklet, and portfolio exemplars became shared resources within the department, helping other teachers integrate ICT meaningfully in creative production and assessment. The multimodal workflows represented here allow all students—including those who prefer visual, auditory, or kinetic processing—to find accessible entry points into the work.

Together, the evidence captures how ICT broadened curriculum opportunities, enabled authentic co-design, and provided a platform for personalised, student-driven creative expression at a senior secondary level.

3.1 — Establishing High-Challenge, Student-Driven Learning Goals Through Co-Designed Multimedia Projects

In the Year 10 Multimedia course, I set clear, challenging, and achievable learning goals by co-designing the learning sequence with students from the outset. The images show the survey, mind-mapping sessions, and the student-driven design flowchart that framed the expectations for the semester. Students selected real-world issues of personal significance, and together we shaped rigorous project goals that required them to research, construct a narrative, storyboard, animate, and produce a final film supported by a full portfolio.

Because goals were co-constructed rather than simply delivered, students understood both the creative ambition and the technical demands of the course. The task outlines, production timelines, and sequential structure (visible in the evidence screenshots) made expectations transparent and scaffolded. Every student worked toward the same high-level outcome — an original animated film — but with personalised pathways, allowing for varied abilities while maintaining a consistently high challenge point. This approach cultivated a studio-like learning environment where students internalised their goals, monitored their own progress, and engaged deeply with feedback to meet or exceed the shared standards of quality we established together.

3.4 — Designing a Resource-Rich Creative Ecosystem Through Student-Driven Production

The Year 10 Multimedia course required students to navigate a complex blend of analogue and digital resources—storyboards, narrative templates, research tools, After Effects, Blender, Photoshop, and collaborative feedback systems. I intentionally curated and modelled the use of this diverse resource set to ensure students could meaningfully translate their ideas into animated films. The images of storyboards, software screenshots, research pages, and production pipelines show how students used these resources as part of a coherent creative workflow.

Because the course was co-designed with students, resource selection was responsive: when students expressed interest in 3D modelling, I introduced Blender; when narrative gaps emerged, I provided sentence stems, planning scaffolds, and visual mapping tools. My modelling of each tool, followed by guided practice and independent application, ensured that ICT became a vehicle for deepened engagement rather than a barrier. This aligns directly with 3.4, as I not only selected and created resources that supported learning, but used student feedback to refine the resource ecology in real time.

4.5 — Embedding Ethical Digital Practice in a Student-Led Production Environment

Because students were creating original animated films anchored in real-world issues, the course required explicit instruction on digital ethics. The images showing research portfolios, narrative documents, and software workflows represent repeated checkpoints where we discussed responsible sourcing of images, copyright, licensing, AI-generated assets, and acknowledging influences in creative work.

Throughout production, I modelled ethical use of ICT: demonstrating how to locate copyright-free resources, how to modify and credit external material appropriately, and how to manage digital files securely within school protocols. Students also engaged in reflective writing about their creative decisions, including where their designs originated and how they avoided replicating existing media.

By embedding ICT ethics within the actual creative workflow — not as a separate lesson — students understood digital responsibility as integral to being a designer. This demonstrates 4.5 at a high level: ethical decision-making became part of the course’s culture, shaping both individual projects and collective studio norms.

5.5 — Building Transparent and Evidence-Rich Reporting Through Portfolio-Based Assessment

The Y10 Multimedia evidence set shows a complete portfolio-driven assessment structure: narrative drafts, research documents, annotated storyboards, software development screenshots, iterative renders, and final animations. These artefacts formed the basis of clear, accurate, and constructive reporting to students and parents.

Because the course was co-designed, reporting needed to reflect each student’s personalised learning pathway. I built a reporting system that captured achievement against shared criteria — creativity, narrative development, technical execution, reflection — while also acknowledging individual trajectories shaped by student choice.

Students received continuous formative feedback through critique sessions and portfolio reviews (visible in the images showing storyboard iterations and digital progress captures). These checkpoints allowed me to maintain accurate records of learning, ensuring that final reports communicated achievement with clarity and fairness.

This aligns with 5.5 by demonstrating:

– rigorous, evidence-based assessment

– accurate reporting grounded in artefacts

– respectful communication of progress and achievement

– reliable documentation through portfolio systems